There are many unique art forms from across the globe and across the span of human existence but few were as influential and original as the art of Ancient Egypt. Their art was not only an expression of the fundamentals of their belief systems and culture, but also served as a vehicle to express the ways in which their society shifted. From a broad overlook, their art evolved slowly over a continuum of time from stiff to slightly more naturalistic -- but this progression was interrupted by one odd, bright moment of deep stylization. This occurred during the revolutionary reign of Akhenaten, the ruler formerly known as Amenhotep IV, who founded a new religion, shifted the capital of the nation and ushered in a new, radical art style known as the “New Amarna style” among other accomplishments -- all of this in a 17 year long rule from approximately 1353-1336 B.C.E. Despite the intrinsic differences, the art of Akhenaten’s reign still has certain similarities to that of his forebears and the Narmer Palette in particular illustrates the similarities and differences when compared to Akhenaten and His Family.

After the death of Akhenaten, the New Amarna style lasted only a few years into the rule of his son Tutankhamun and then Ancient Egyptian art as a whole returned to its traditional roots. However, the importance of the New Amarna style cannot be understated. The most significant principle of the New Amarna style was how human subject matters were depicted: in a departure from the stiff posture and stylized gesture, the humans were warped in a sense. Bodies were rounded and exaggerated: with protruding lips and bellies, stark clavicles, elongated faces and heads and almond shaped eyes. This was an attempt at naturalism that deeply overshot and become its own style that was neither realism nor traditional. The difference between the old and new styles were especially striking in royal portraiture where Akhenaten was depicted in combination with traditional symbols such as the crook and flail that had undergone no such change.

The Akhenaten and His Family relief embodies the New Amarna style perfectly. Created in the Eighteenth Dynasty around 1353-1336 BCE, it was a sunken relief (a subtractive method of creation deeper than the standard relief carving) on a limestone medium that was once painted but the pigment has since faded either due to long exposure and wear, or the failure of its binder. The actual texture of the limestone was sanded and polished down to create a smooth surface for the incisions of the artist but the grain is still faintly present. The buttery ochre of the limestone, whether due to natural aging or a conscious choice of the artist’s, reinforces the importance of the sun depicted in the upper center of the carving. Lacking a knowledge of Egyptian hieroglyphics, the incised language of the ancients creates a contrast between the smooth expanses of the panel and contributes to the general texture of the piece.

The scene appears to narrate a usual day for the royal family during Akhenaten’s peaceful rule. The two main figures of Akhenaten and Nefertiti facing each other create a sense of bilateral vertical symmetry, balance and also create implied lines of sight between them as they look directly at each other. Looking at the eyelines and the way they are depicted, hierarchal scale is subtle feature in this work but the main connotation of rank would be the fact that Nefertiti’s eyeline is lower than his. Traditional gender depiction is also present in the fact that Akhenaten’s shoulders are broader than hers and that he is larger in overall size. Despite having the typical New Amarna lips and softness, they are still depicted in a composite pose with the head in profile and the body angled towards the viewer. This composite pose also helps to convey a slim sense of space by overlapping the feet. The empty space left in between the limbs and the bodies of the figures of this carving also help to convey some two-dimensionality. Their bare feet rest on a spiritual anchor line, sacred ground.

Their children in particular illustrate the New Amarna penchant for elongated heads to an almost disturbing degree. They are also shown in deeply realistic and informal poses as they play and fidget on their parents laps, emphasizing that this was a work of peacetime and leisure. They do not hold as much visual weight as their parents do, and the smallest child on the shoulder of Nefertiti sometimes goes unnoticed by the casual viewer. In the children’s forms, the representation of age and hierarchal scale combine. But even the king and queen are not the most important figures in this work despite being the largest. Instead, the focal point of the piece is the deeply incised sun, carved with a much heavier hand than the rest of the work in order to create an emphasis on it. The sun was one of the most important aspects of daily Egyptian life: giving warmth, light and nourishing crops, and was therefore represented in a multitude of different gods throughout the history of Egypt. The diagonal lines that shoot out from it towards the ground imply the rays of the sun (the god of which is the only deity in Akhenaten’s new form of religion) and the rapid visual speed with which they travel to grace the land of Egypt. Visually, the rays also remind the viewer of the pleats of in the clothing of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, and those pleats create a sense of compressed volume otherwise lacking in the carving. Actual line is repeated constantly throughout the piece to give a sense of structure that contrasts against the softness of the bodies of the humans and creates an artistic tension.

The thrones on which Nefertiti and Akhenaten are seated are nondescript but important nonetheless: the queen’s is decorated with stylized flora (likely papyrus and lotus) to symbolize her role as a life giver and perhaps reinforce her femininity, whereas her husband’s has a geometric motif featuring a rectangular pillar flanked by two right triangles that could represent his strength and solid power. Geometric shapes are repeated in their footstools and in the floor beneath their feet, also contributing to a visual atmosphere of structure.

The Palette of Narmer is a much earlier creation from approximately 2950 BCE and was carved from green schist with no trace of added pigmentation. The Palette is also a relief and a subtractive art form, like Akhenaten... and is smoothed and polished in a similar way the limestone carving was. However, it also conveys a much more complex narrative than a simple scene of daily and parental life: the struggle and triumph of a legendary king in multiple registers on two sides of the same piece. There is also more diversification of figures depicted -- from humans to gods, animals to mythic creature. However, the composite pose featured heavily in the Palette is also seen in Akhenaten... and helps to convey space and dimensionality in a similar way. The composite pose is one of the most striking similarities between the two works of art, and illustrates a principle of Egyptian art that underwent very little change across the millennia. Hierarchic scale is also much more emphasized in the Palette of Narmer: the smallest figures are not small because they are young children like Akhenaten’s princesses but they are actually prisoners of war or low-ranking soldiers. But Narmer, like Akhenaten, has broad shoulders and is the largest figure in the piece. Facial features in the Palette are all depicted along the traditional lines, nothing emphasized or warped, maintaining strict stylization -- there is little individualism among the human figures, least of all the decapitated prisoners of war and soldiers.

The narrative of the Palette is much more complex than the limestone carving, and the multitudes of figures and violence create a more chaotic atmosphere -- perhaps reflecting the political situation of the era in which it was created. The deepest incisions of the Palette not only emphasize the importance and otherness of the quasi-lions in a similar way that Akhenaten and His Family places emphasis on the godly sun, but also serve a functional purpose to perhaps hold cosmetics for application. Unlike the Palette and its ability to be held and passed from hand to hand, the carving of Akhenaten… is designed to be looked up at and featured, not touched by the many. This functionality is deeply at odds with the respective purposes for each piece: the Palette depicts a king ritually slaughtering his enemies whereas the carving shows a domestic scene with a more human king acting like any other Egyptian and showing affection towards his family. Obviously, each form has their own significance but the deeper nuances and subtleties of the artists choices are now lost to the modern viewer.

In conclusion, the Narmer Palette and Akhenaten and His Family share the same cultural roots and express those roots in some similar ways like pose and hierarchic scale, but are also fundamentally different in their meaning and execution. Neither of these works are intrinsically better or more important than the other, but must be considered as the products of the eras that they were created in. If either of these works were to be lost to the sands of time, the history of Egypt would be irreparably damaged as would the history of art.

------------------------------------------

The relief sculpture Akhenaten and His Family is a piece of art from Akhenaten, known today as Tell el-Amarna. The artwork is from the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt and can be viewed in the Ägyptisches Museum. It was made sometime between 1353 and 1336 BCE during the reign of Akhenaten. During his17-year reign, Akhenaten not only moved the capital of Egypt north but he also brought a new style of art to Egypt. He developed different distortions to the way rulers were portrayed and created a form of androgyny in the art. This specific relief portrays the family life of Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti. Both the king and queen are seen sitting on cushioned stools holding their daughters. Their daughters are portrayed with elongated, shaved heads to show the new figure type of the time. They are all shown in composite poses, meaning that their torsos are facing out with their waist and legs pointing towards each other. This creates a twist in the body. The couple is shown receiving blessings from Aten, the sun god, as the rays with arm like ends reach through their pavilion and extend towards their nostrils. This is seen as giving them the “breath of life.” The three children are in different poses. Unlike past art the children are shown more realistic. Past pieces show children in a pose of serenity. This relief conveys the children’s fidgety behavior through the way they are posed. The king and queen are shown having loving interaction with the children, differing from previous art where there was little interaction between figures.

Akhenaten and His Family is a royal portraiture created to depict the King and Queen with their family in the form of a painted limestone sunken relief. A relief is a type of sculpture where the sculpted elements remain attached to the solid background that is made of the same material. A sunken relief is much different than a regular relief sculpture. In a regular relief the background is carved back so that the figures seem to project out of the surface. However, in a sunken relief the original flat surface of the stone is reserved as background and the outlines of the figures are deeply carved to develop a three-dimensional form. The medium in which the relief was made was limestone, a relatively soft rock that is easy to carve. It was made by carving the stone deeply to create the three-dimensional figures that appear in the relief. The carving was most likely done with a harder stone in a subtractive process. This means that the artist carved away the limestone rather that adding a substance to the limestone to create the sculpture. As mentioned before, the deeper the carving, the deeper the shadow creating more dimension in the relief. The image of the king and queens lovingly interacting as a family is captured through the use of elements such as line, space, repetition, shape and texture. This was one of the first pieces of its time to show feelings between families along with realistic depictions of children’s behavior.

The majority of this piece along with many pieces of artwork is made up of lines, both actual and implied. Lines can be viewed as “the path of a moving point,” they are used to describe the direction of a plane in space. They help to guide a viewer’s eye throughout the artwork. In the relief Akhenaten and His Family, the lines that outline the image seem to frame the scene causing a viewer’s eyes to focus on what is inside the frame. There are also implied lines that appear on the King and Queen’s clothing. It makes it as though their clothing is textured and flowing. There are also lines that are used to represent the sun rays. They show the direct path of the rays. Shadow and depth are seen around the figures, this is created through the use of a thicker, deeper carved line. This concept is also seen in the faces, creating a contoured jawline of both the king and the queen. Also, the line in the king’s neck can be almost viewed as a vein. The curvilinear line that creates their scarves creates a sense of movement from the wind. Line has the ability to create a movement that is not actually there.

Space and shape are also crucial parts of this work of art. There is a strong depiction of space to create a scale of the images. One example of this is the difference in the sizes of the children versus the queen versus the king. King Akhenaten is portrayed sitting slightly higher than Queen Nefertiti and is also slightly taller. This use of hierarchical scale shows the difference in their power and natural size by the scale used. The children are also significantly smaller that the king and queen suggesting that they are in fact their daughters. The children are also all different sizes to display their differing ages to the viewer. The space carved out around the figures shows the depth and movement of the figures depicted.

Texture and repetition are also prevalent elements of this relief that help to provide balance and a symmetrical composition. The repetition of the sun’s rays spanning the entire image show the importance of the rays. They were seen as the breath of life being sent from Aten, the sun god. The sun god was very important to the Egyptians. Through the repetition of the rays the viewer understands that the king and queen had the support of Aten, and therefore were adequate leaders. The sun rays divide the image and show the symmetry of the relief. Texture is shown primarily through the king and queens clothing. Their clothes look wrapped and draped around their bodies. The relief also uses texture to create the human look of skin.

Darius and Xerxes Receiving Tribute-Relief from the stairway leading to the Apadana, Persepolis, Iran. 491-486 BCE. Limestone, height 8’4’’ From the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

One piece of art that can be compared to Akhenaten and His Family is the relief Darius and Xerxes Receiving Tribute. Darius and Xerxes Receiving Tribute is a relief that is part of the stairway that leads to Apadana in Persepolis, Iran. The piece dates to 491-486 BCE, significantly younger than Akhenaten and His Family. It is approximately 8’4’’ tall and can today be seen at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. This relief depicts a scene from Darius’ rule. He came to rule the Persian Empire after the death of Cyrus II. Darius built Persepolis with influence from Persia, Mesopotamia, Greece and Egypt. Xerxes is the son of Darius. In the relief the viewer can see Darius sitting on a throne holding an audience while Xerxes listens from behind.

There are many similarities that can be identified between Akhenaten and His Family and Darius and Xerxes Receiving Tribute. One of the most noticeable similarities is the medium that they are made out of. Both reliefs are made out of limestone. Akhenaten and His Family is made from painted limestone and Darius and Xerxes Receiving Tribute is made from limestone. Another similarity is that both of the pieces are reliefs. This means they were created in a subtractive process. The images were carved from their background to make it look as though the image is protruding from the background. Another similarity is the way in which texture was used to show the draping of the clothing that the figures wear in both figures.

While there are many similarities between the two pieces there is also some distinct differences. One difference is the way in which the figures in the images are portrayed. The people represented in Darius and Xerxes Receiving Tribute are posed rigidly on an anchor line like most Egyptian works. There is also very little interaction between the figures. There is little to no variation in the faces of the figures in the relief. The figures in Akhenaten and His Family are shown in more natural poses and there is an abundance of interaction between the figures. The king and queen are shown holding their children and showing them affection. Their feet are not placed on an anchor line and instead show the depth that one leg is behind the other. There is also much more detail in the contouring of the king and queens faces as opposed to Darius and Xerxes Receiving Tribute. Another difference is the type of image that is portrayed. Both images are that of a leader but Akhenaten and His Family shows the leader in a family setting and shows the realness of his life. Darius and Xerxes Receiving Tribute shows the leader in a superior way, sitting on a throne.

The relief Akhenaten and His Family uses many technical elements to portray the family dynamic of King Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti. The elements used to bring the relief to life are line, the depiction of space and shape, repetitive shapes and texture. The way the elements work together to create the image show the shift in style during King Akhenaten’s rule. In comparison to the relief Darius and Xerxes Receiving Tribute there is significantly more detail and shape to the individuals depicted. Akhenaten and His Family is carved deeper to create a three-dimensional image that shows the family lovingly interacting in natural, realistic poses.

Reference

Stokstad, Marilyn, and Micheal W. Cothren. Art History. 5th ed., vol. 1, Pearson, 2014.

Analysis of : Akhenaten and His Family, Painted Limestone, 1353-1336 BCE

The limestone stela of Akhenaten and His Family depicts the noteworthy Eighteenth

Dynasty king alongside his queen, Queen Nefertiti, and three of their young children. The icon,

which was intended to be kept in the private, innermost chapel of a house in the ancient

Egyptian city of Tell El-Amarna, is sculpted with a scene of an “intimate moment from the daily

life of the royal family” below an aten, a disk representing Ra, the sun king (“Stela”). Though

Akhenaten is sitting rather relaxed and comfortably across from his queen on a low, cushion-

topped stool, link is still strongly emphasized between the king and his cherished god. The era of

Akhenaten, commonly known as the Amarna period, was a time of great change in ancient

Egyptian society.

Adopting the throne in roughly 1353 BCE, young Akhenaten was tossed into the position

once held by a considerable line of military-driven predecessors. Nevertheless, his drive was

documented well beyond that of war strength. Besides moving the capital from Thebes to the

north at Amarna and calling himself “Pharaoh” for the first time, the father of nine had

drastically altered religious and cultural life in Egypt. As represented in the stela, Akhenaten

defeated the typical, polytheist, mindset and raised the solar god, Ra, to the ultimate position of

'sole god' in the minds of his people. As a monotheist establishment, Egyptians soon cherished

Ra and the belief that, when the sun rises, it eliminates all of the harmful, unsolicited things that

come out during the darkness of night (Spence). Additionally, Akhenaten changed the typical

artistic conventions of the time period, often resulting him as being characterized as the “first

individual in human history” (Spence). Though still highly stylized in proportion and feature,

human figures start to become portrayed in naturalist means, in which actually resemble the real-

life individual. The royal family is depicted in works of this era with identifiable faces and

realistically full hips, thighs and stomachs, unlike ever before. Subsequent to these changes,

Akhenaten also instigated alterations to temple construction and pressured that structures be built

from much smaller stone (Spence).

The stela of Akhenaten and His Family, in particular, is considered an historical

masterpiece. The piece’s sculptor, utilizing the sunken relief technique, took advantage of

multiple elements and principles of design to make the piece, as a whole, visually interesting in

all aspects. By use of the subtractive process, chiseling away at the large stela, the element of

line was used to depict linear hieroglyphics in the background paneling, to outline the furniture

and royal figures, and to also depict sun rays symbolizing their cherished Ra. The general

space of the relief depicts a symmetrical, face-to-face couple embarking on the task of parenting

in nearly full-proportional scale. Though their arms are narrow and their faces are triangular with

stylized features, the lower bodies of the individuals are, as previously stated, developed with

full, healthy stomachs, realistic hips and lifelike thighs. Balanced on an anchor line, the artistic

convention developed by the Egyptian peoples to ground their figures, the royal couple depict a

dominant, horizontal appearance while the written language is lined vertically down the large

stone. Though Akhenaten and his queen are sized to fill nearly the entire stone slab, in the

means of hierarchical scale, the complex composition of the relief does not override the

emphasis placed on the power and authority of the couple.

Although the stela is made of limestone, which is very hard and lightly textured to begin

with, this relief sculpture maintains a very peaceful relationship between line and texture. The

engraved lines defining the fabric of the Egyptian king’s clothing are repeated on that of Nefertiti

and create a distinct ruffled texture that draws in the viewer's attention. The cushions they sit

and rest their feet upon are made up of rounded, heavily shadowed lines that imply an incredibly

plush and soft look, even though they are truly the same medium and harness as the rest of the

piece. Such thoughtful combinations of naturalistic technique became typical of the Amarna

style artwork of the period.

The repetition of triangular and curvilinear forms is also rather noteworthy. Contributing

vastly to the overall flow of the piece, the deeply incised, triangular shapes, are found in the

positive space of the blue crown as well as in the negative space of the footwear, stools, and

sun rays. Whereas the circular, more curvilinear shapes, are found in the adult eyes, the tops of

the foliage, the shapes of the children's heads, the seating, and in the bodily silhouettes. These

forms are striking and show the dedication the sculptor contributed to its construction.

One of the best pieces to compare this stela of Akhenaten and His Family to is titled;

Assurbanipal and His Queen in the Garden, c. 647 BCE, from the palace at Nineveh located in

modern day Iraq. This alabaster, 21 inch high, panel is a prime example of Assyrian art from the

Ancient Near East and is designed to leave an impression similar to the Akhenaten stela. The

relief depicts a ruler and his queen in a well-respected atmosphere, relaxed and enjoying the

everyday blessings of life. The narrative concept and technical use of horizontally-focused,

low-relief carving into a stone medium is almost synonymous between the two pieces.

Additionally, the inclusion of stylized figures, foliage, and general emphasis on line and

curvilinear forms is exhibited in both works.

Nevertheless, there still remains a few differences between the two historical pieces.

Above all, the composition of the royal couple does not overtake the entire relief as it does in the

Akhenaten and His Family stela (Locking). The viewer is not overwhelmed by the figures and

more attention is dedicated to the background objects and narrative of the situation. Unlike

Akhenaten who is seated in an upright position, Assurbanipal is in a reclined position

surrounded by eager servants. This carving is also far more asymmetrical than the Akhenaten

stela. The ruler and his queen are offset to the right side of the piece and are not locally

dominant in the center. The alabaster relief is distinctly absent of children, a focalized aken,

and, given the softness of the stone, provides a much more detailed scene. Though those are

some major differences that should not be overlooked, the heart of the work is definitely still

there. Both royal couples were deemed to be cherished by all.

In essence, the limestone stela of Akhenaten and His Family is a work that will forever be

considered an artistic masterpiece. Now located in the Egyptian Museum, in Cairo, the 43.5 cm

by 39 cm stone stela is well preserved and will be observed by many more generations to come.

Akhenaten was one of the most unique rulers of ancient Egypt and carries along with him a

lengthy legacy. His dedication to family life and pursuance of change in the Egyptian society

made him unlike no other. The 1912 discovery of the Akhenaten stela was groundbreaking and

helps us to better understand the extraordinary ancient culture of the Egyptian people.

Works Cited

Locking, J. "Ancient and Medieval Art." Assurbanipal and His Queen in the Garden. N.p., 05

Oct. 2011. Web. 24 Oct. 2017.

Spence, Dr Kate. "History - Ancient History in Depth: Akhenaten and the Amarna Period." BBC.

BBC, 17 Feb. 2011. Web. 24 Oct. 2017.

"Stela of Akhenaten and His Family." The Global Egyptian Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Oct.

2017.

Analysis of: Akhenaten and His Family, painted limestone relief, 1353-1336

Akhenaten ruled over Upper Egypt for seventeen years, these years ranging between 1353 B.C. and 1335 B.C, most well known as the Amarna period. Beginning his reign, his throne name previously had been Amenhotep IV, although during his sixth year as ruler he changed his name to Akhenaten, this translates to, “benevolent one of (or for) the Aten,” (Jarus). Akhenaten was also the first to call himself “pharaoh” within Egypt. As a father of nine, he was assisted through his reign by Queen Nefertiti, also known as the, “Ruler of the Nile.” During Aten’s time as king, he had crucially converted the entire country, starting an entirely new religion solely

praising one single god, in contrast to the previous polytheistic views; this specific god supplying life, known as the sun deity Aten, which was later shown within different sculptures as the sun’s disk. While a new religion was being created, Egypt’s capital had also been moved north. Thebes had been Egypt’s capital long before Aten’s reign, and during his time as King, the capital had moved north later being called “Akhenaten.” The newest style, the Amarna Style, also arose during this time. This new found style created an entirely new view on stylized sculptures, created extremely detailed and exaggerated features. Akhenaten’s reign created a new contemporary view that Egypt previously hadn’t been exposed to.

The Egyptian relief sculpture, “Akhenaten and His Family,” shows Akhenaten's family as a, "Holy Family," (“Stela of Akhenaten and His Family”). This relief, painted limestone, displays the sunken relief technique; this being a subtractive processes by removing the stone, or media, with chisels and mallets. This specific piece, ranging in size by 12-¼" X 15-¼", shows both Akhenaten and Nefertiti sitting across from one another with three of their daughters. Also shown within this relief is Aten, represented by the sun's disk centered at the top of the piece. The use of the new Amarna style depicted throughout this relief is seen by the stylized faces where it is now legible to see who is in the photo. As both the King and the Queen are depicted in cushioned stools, they are both relaxed and seen as having sagging stomachs, which hasn’t formally been depicted before. The relief embodies every impactful change that King Akhenaten brought to Egypt, from his family and their powerful reign, to moving the capital to Akhenaten (“Horizon of the Aten”), displaying within the “horizon” of the piece, shows the new, profound religion shown by the representation of the sun’s disk and lastly the detailed work that was known as the Amarna Style, (Stokstad). With three of their daughter portrayed within the piece, they are shown as relinquishing loving involvement with their parents, and not shown as posed and full of serenity, (Stokstad). Two of the daughters are pointing to both the Akhenaten and Nefertiti, as the third is pointing to the god, or the sun. These simple gesturing of hands represents the afterlife the god supplies those who pass on, which is simply what the Egyptians worshiped, the afterlife.

Within this piece, it is clear to see that many different elements of design were prevailed throughout. One of the most dominant elements include the usage of line. From clean cut, to curved edges, and continues lines were strictly incorporated in delicate ways to portray the sole meaning of the piece. The radiant repeating beams extruding from the sun’s disk landing at both the king and queens’ nostrils, represents the god supplying them with the, “breath of life,” (Stokstad). The use of curved lines beneath both Akhenaten and Nefertiti allows for them to be shown in a relaxed, carefree way. As they are also shown in a slouching manner, this may in a way represent both their power and nobility, not having the worry about much due to their royal standings.

Not only lines were used throughout this piece, but it was also accompanied by the use of shapes. Shapes are a universal language that can overall depict many different stories based on how the author decides to incorporate the pieces. The most prevalent shape depicted in the piece, “Akhenaten and His Family,” would be the circle centered at the up most part of the relief. This is not only a circle, but the representation of the common god during this time, known as the “life-giving sun deity Aten,” (Stokstad). While incorporating this universal element of shape, it is also prevalent to see that these are two people of royalty, due to the pharaoh and queen’s headdresses that detailed by different shapes atop their heads. The plant like structures beneath Nefertiti can also be viewed as the growth of living objects, receiving their energy and strength from the sun above.

Texture is a key component to being able to depict which material was used to create the piece of art. This specific piece is created from the hard sedimentary rock limestone, it is prevalent to see due to the texture atop the piece. With the large piece missing from the top, upper left-hand corner, it is obvious that the interior of this color does not match the exterior; this meaning that the piece was painted with some form of paint pigments during the time. As this piece represents the sunken relief technique, this means the foreground of the material used is what is being sgraffitoed in order to create reliefs that are deeply incised into the media itself. The balance shown throughout the piece is seen as symmetrical, with the center shown as the sun above. Scale is another extremely important element, especially during the Egyptian time. The hierarchy scale was implemented in order to show the power of one to another based on their size in comparison. These lines can also represent how the sun above them supply them with life and can be the outcome of why both Akhenaten and Nefertiti are at the scale size they are.

Stele of Naram-Sin, Sippar, 2254-2218 BCE.

When analyzing Akhenaten and His Family, it similarly reminded me of the Stele of Naram-Sin. This stele, similarly to Akhenaten’s was made from limestone, was formed in

Sippar, common day Iran, having a height of nearly six and a half feet tall. Within both of these pieces, there is a central viewpoint of a sun or moon at the upper most part of the media. While within Akhenaten’s piece of art, there were rays protruding from the sun, the mountain beneath the sun in the Stele of Naram-Sin can represent the same idea; with the lines that display the sides of the mountains can be viewed as the sun’s rays extending down to those beneath the god. It is prevalent to see throughout Akhenaten and His Family, that due to the large scale of the figures they are of royalty, it is clearly depicted that the hierarchical scale is shown within the Stele of Naram-Sin; the pharaoh seen at the top of the piece is shown with a headdress and displayed at a larger scale compared to the figures below. The tree like figure can as well be receiving life from the sun’s beams, indulging in the sun’s nutrients. Although, unlike Akhenaten and His Family, the Stele of Naram-Sin is a relief carving. While using the subtractive process, or carving away from the media, the photo depicted is left risen. Akhenaten’s piece is a very horizontal, while looking into the Stele of Naram-Sin your eye move in a zig-zag pattern vertically in order to read the piece. Also, while in Akhenaten’s piece a symbolic view of family is depicted, the stele shows a war taking place, as soldiers are falling, and others are rising to take the deceased place, (Khan).

Akhenaten created an entire new feel for Egypt during his time as King. The piece “Akhenaten and His Family” solely incorporates every new part of Egypt throughout his seventeen years of reign. The artist’s use of shape, texture, line and scale help depict these revelations shown. The new stylized technique allows those viewing the piece to be aware of whom specifically the art is about. Previous artwork like the Stele or Naram-Sin can show the same idea or feel, but with what Akhenaten brought to Egypt during the Amarna period created an entire new feel for art at the time.

Works Cited

Jarus, Owen. “Akhenaten: Egyptian Pharaoh, Nefertiti's Husband, Tut's Father.” LiveScience,

Purch, 30 Aug. 2013

Khan Academy. (2017). Victory Stele of Naram-Sin

“Stela of Akhenaten and His Family.” The Global Egyptian Museum | Stela of Akhenaten and

His Family

Stokstad, M. and Cothren, M. (2011). Art history. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice

Hall.

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin | AHA, www.historians.org

---------------------------------------------------------------

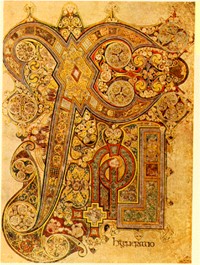

Chi Rho Iota

The Book of Kells

Collection: The Board of Trinity College, Dublin, IR

In the 5th Century, Roman power in the Western Empire starts to dissolve with the rise of the Barbarian culture among other massive imperial powers. At this time, the Barbarians start to reshape what once belonged to the Romans and later, the Vikings begin to patrol the seas in their impressive ships with every intention of conquering what once belonged to another society. During all of this war and conquering, an island sits quietly off the Scottish coast. On this island, a religious monastery was the home of vocational monks, known for their teachings, art production, and havens for those who sought to learn the word of God. This holy place was home to an individual who would soon be known as one of the most influential Christian saints of all time, St. Columba. St. Columba was an Irish abbot and missionary, credited with spreading Christianity in what is modern day Scotland, at the start of the Hiberno-Scottish mission. Accompanying St. Columba, were numerous Celtic monks, who were responsible for the writing and artistry involved in the creation of what is known as The Book of Kells. This religious artifact contains the four Gospels written by the apostles Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. With the help of divine inspiration, each apostle relays the stories of Christ’s life, ministry, and death through his own personal experiences. These gospels were translated in Latin based on the Vulgate text which St. Jerome completed in 384AD, intermixed with readings from the earlier Old Latin translation (www.tcd.ie). The real point of the Book of Kells seems not so much the text, as it is the art work that houses it, and the embellishments applied to the calligraphic text (1 Lubbock). Even with limited materials, these Celtic Monks created one of the most beautiful works in all of religious art. With God as the author, these monks skillfully illustrated what is known to be a tabernacle for the Word of God.

Throughout the whole text, historians find delicate and ornate designs accompanied by

intricate swirling and complex detail, but the most famous of all is said to be The Book of Kell’s,

Chi Rho Iota page. This page in the Book of Kells is based on the verse from Matthew 1:18 that in English in the 1611 version begins “Now the birth of Jesus Christ was on this wise: When as his mother Mary was espoused to Joseph, before they came together, she was found with child of the Holy Ghost.” This passage is often referred to as the second beginning of Matthew. The Latin text, the one used most commonly in medieval manuscripts, begins “XPI autem generatio . . .” (1 Spangenberg).

The creators of this piece used line to give the illusions of movement and majesty. Line placement, along with color, captures a grand design composing Greek letters. Chi and Rho are two letters of the Greek alphabet, the first two letters of "Christ". Chi gives a hard Ch sound. Rho is an R. Chi is written as an X. Rho is roughly a P (1 Lubbock). In this piece letter placement is obviously extremely important. Chi is the dominant form, an X contributes an asymmetrical design being uneven in nature. All three letters are decorated with remarkable embellishments, discs, and spirals. Throughout the piece we see animals and angels within the letters. With the depiction of four separate beasts, historians note these images to be symbolic and representational of the four evangelists (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) responsible for the scripture within the book itself. Another aspect of this work of art that historians think to be symbolic is how the letters were shaped in general. According to Tom Lubbock from Independent Art, “They have been shaped with a view to the patterns they will be part of, and they are themselves filled and formed by ornamental elements, like the diamond that makes the hinge of the X, and the head (Christ's?) that oddly finishes the P's spiral”. The use of diagonal, horizontal, and curved lines suggest a tranquil yet regal balanced appearance to this piece. The artists also utilize the formal element of scale. The fact that the Chi Rho itself is immense, using the space of the entire page, alludes to the fact that God is universally all encompassing. One could look at this as hierarchical scale simply using letters.

These manuscripts were referred to as illuminated in view of the fact that they captured light and reflections so well due to the artist’s particular use of extraordinary color. The color pigments used, such as yellow, red ochre, indigo, green copper, and an extremely rare lapis lazuli (which came from Afghanistan) gave this piece a superb characteristic that is hard to compare (1 Kearney). The intention of the artists in employing such a high value of pigments was to give the observer the experience that he/she was looking at a piece of sacred art, actually aglow with light from within (Pepper Notes). As stated before, within these pages reflected the Word of God. Christians believe Christ’s first coming was when God made the Word flesh (Pepper Notes). Interpreting this scriptural story, The Father said He would send His Son to bring about the kingdom of God and therefore, the prophesy was fulfilled; Christ was born. In a similar way, these beautiful pages needed to be equivalent to the majestic throne that God sits on. In the eyes of the Christians, these pages needed to be worthy enough to house the Word of God. Meaning, the monks spared no expense of money or time in using the worthiest of colors in creating these pages.

Some historians tend to call this work abstract; however, others would disagree. These forms are not autonomous; they are decorations and devotional pieces of what they encompass all together, God (1 Lu). The monks’ way of honoring, or in this case worshiping someone, was through their sacred art. Since God is so good, so fulfilling, and omnipotent not one single space should be left undecorated. The artists used space to represent how loving and worthy their God was. Form, space, and line collaborate together to show a never-ending, somewhat doodling effect, causing the viewer to see no beginning and no end (Pepper Notes). Through the use of

these formal elements, the monks told the story of how God has no beginning and no end. Their format reinforces their belief that God is the Alpha and the Omega. His reign is eternal and continues on even past the end of time. This aspect of infinity is seen throughout the whole manuscript. Due to the fact that this form is so intricate in nature, some art historians and those who study art in general seemed to believe that this work was the work of angels and not of man. Their reason being, the colors being so vivid yet the design being so small, full of turns, twists, and swirls.

It was clear that the monks creating this wonderful page had a plan and strict purpose. During this time and still today, when religious artists begin to capture their craft, they look at their abilities as gifts from God and try to channel God’s beauty in all they create. St. Columba’s monastic community truly captured the majestic nature of their God through intricate design, space, and color.

It was clear that the monks creating this wonderful page had a plan and strict purpose. During this time and still today, when religious artists begin to capture their craft, they look at their abilities as gifts from God and try to channel God’s beauty in all they create. St. Columba’s monastic community truly captured the majestic nature of their God through intricate design, space, and color.

Works Cited

Kearney, Martha. “Culture - The Book of Kells: Medieval Europe's Greatest Treasure?” BBC, BBC, 26 Apr. 2016, www.bbc.com/culture/story/20160425-the-book-of-kells-medieval-europes-greatest- treasure.

Lu, Alan. “Understanding Art 1: Western Art (Learning Log).” Unit 4: Annotation: Chi Rho Page (Folio 34r) Book of Kells, 1 Jan. 1970, alanarthistory1.blogspot.com/2011/03/unit-4-annotation- chi-rho-page-folio.html.

Lubbock, Tom. “Anonymous: The 'Chi-Rho' from 'The Book of Kells' (C.800).” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 15 May 2008, www.independent.co.uk/arts- entertainment/art/great-works/anonymous-the-chi-rho-from-the-book-of-kells-c800- 828951.html.

Spangenberg, Lisa. “XPI Autem Generatio: The Book of Kells and the Chi-Rho Page — Celtic Studies Resources.” Celtic Studies Resources, 28 Apr. 2017, www.digitalmedievalist.com/2010/12/25/xpi-autem-generatio-the-book-of-kells-and-the-chi-rho- page/.

Research Paper # 2

Jeweled cover of The Lindau Gospels, France, workshop of Charles the Bald, c. 870-880 CE. Housed in the J. Morgan Library in NYC.

In the ninth century the front cover of the Lindau Gospels was created by Folchar, one of St. Gall’s preeminent French artists. It was made around 870-880 CE in Eastern France. On the front metal cover you can see Jesus Christ in the forefront. He is centralized in the composition because he symbolizes the central theme of Christianity due to his crucifixion and what occurred following. It also shows Christ being the largest as compared to the other human forms. He divides the codex book cover into symmetrical parts. Additionally, the composition symbolizes balance, both visually and spiritually. The material gold shows how important Christ is to Christianity. The makers of the metal book cover used only the finest of materials. The jewels and materials symbolize extreme value and richness which act also as Christ’s importance. Religion was a big part in medieval society, especially monks. Monasteries through Western civilization were great centers for creating liturgical and religious artifacts. Early Christians took religion extremely seriously and followed all the rules that the priest practiced and taught. The Lindau Gospels was produced to have the four gospels contained within it. The four writers of the Gospels who are Evangelists (meaning “they are the messenger of good news”), their names were: Luke, Matthew, Mark and John. Each Gospel had a different painting that represented their story and symbol.

The interesting thing about the book that caught my attention is that the front, back and manuscript pages were made in different parts of the world. The metal cover that held the illuminated Gospels was made in France by Charles the Bald’s workshop, the back was made in Salzburg, Austria and the manuscript pages were made in Switzerland. I found this so interesting because it makes me wonder how the book was passed from one artist to another and traveled around to different countries and was never broken nor stolen. Keeping the Gospels intact shows incredible devotion in itself illustrating how devoted medieval people were, especially guilds and monasteries. Another important factor was the spreading of Christianity through The Word of God. As Gospels traveled, so did the Christian message and many people valued the words contained and respected it. This may be one reason why the Gospels were never ruined because they believed so fully in Christianity and knew Christ was watching.

The Lindau Gospels contains the four Gospels with supplementary materials like: the prologue of Jerome, prefaces for the gospels that were in the manuscript, chapter listings and twelve richly illuminated tables on a purple background. The purple background may have possibly been made from Ox Gall ink which is made from the liver of a cow mixed with alcohol. Also, seven different scribes were engaged in the copying of the words in the manuscript. The letters are in gold and silver illuminating “The Word of God” both physically and spiritually . In each different ‘book’ there are different paintings and different colored backgrounds that make each book unique and special. The importance of the gospels was that monks understood the gospels as an act of mediation and only wanted to show their devotion through the making of religious objects. The monks respected the manuscripts because of their importance of what the contents stood for, The Word of God. The metal cover of the manuscript is repousse which means to “push up” or chased to shape the ten small figures as well as Christ who is in the center of the front cover. In a way it’s a type of metal relief.

The front of the metal cover has different colored jewels that catch your attention and make you wonder how it was created. The gold is the background of the cover and the jewels are encrusted in the gold. Some of the colors of semi-precious stones both are primary and secondary colors that are shown such as: green, silver, baby blue, red, black, brown. The jewels on the outside of the cover seem almost fruitful meaning rich, colorful and vibrant, as they protect a fruitful scripture on the inside. Both inside and outside match the lavishness and show how rich the early medieval culture was. This also illustrates how the monks were devoted and appreciative of their culture and wanted it to be symbolized in the book of Gospels. Because of the scripture’s significance, the artists wanted the book to be remembered for its beauty and luxury.

The book inside and out has a lot of meaning spiritually and physically. The crucifix is in the center because Christ is the center of Christianity. The symbolism that Jesus Christ is showing the viewer is that he is strong and confident and is always there for his followers. That is why he is hanging brave and almost fearless it seems. There is no suffering in his face, the only suffering that viewers are able to see is the blood dripping from his hands that have nails in them. Jesus is chased from a metal sheet covered in gold because of his status and the level that other individuals cannot reach him. Compositionally, Christ hangs symmetrically from the centralized crucifix. He is also the largest human figure on the cover. The ten smaller figures around him are also gold are very important as well because they also reach that richness due to their relationship with Christ. The significance of how their representational forms are being used, is that they have historical value. Each smaller unit or “cell” tells a special story in Christ's life like rectangles we have seen in other sequential art pieces. For example, this same story is still being used today to teach me about Christianity background and its meaning to the Christian faith in general.

The cover is fully symmetrical and a balanced design. The lines in the front of the cover separate the jewels from the smaller figures and those figures from Jesus Christ so everything appears to have a visual boundary. Some of the figures surround the crucifixion are: Virgin and John and Mary Magdalene and Mary, the wife of Cleopas. The back of the book has a lot of small designs which make it extraordinary as well. Each design is very eye catching and different from the front. Both covers of the book are symmetrical and everything is divided into balanced sections. Jesus Christ is central to Christianity as well as being central in the balanced composition. Christ being in the center with his arms stretched outwards divides the cover in each of the four corners. Each corner may represent the four Gospels. There are six rectangles in total on the front cover. Firstly, there is a big rectangle of the container itself, more rectangles appear inside that rectangle. This book shows a lot of repetition and pattern. For example, in the front of the book the cover has jewels on four sides. The figures are in the four rectangles. The back of the cover has the same pattern around the middle of the red jewel. Around all four sides of the container is surrounded by jewels. There are four ancient Roman arches with human figures dressed in Hellenistic clothing with crossing arms. The leaf shaped design that is on the back has swirls as well. The four corners of the rectangle that are at the edge of the back cover have human figures chased in them too. Everything is filled up with some type of design. In the front of the book the only space that is available is around Christ who hangs on the cross. When it comes to scale, Christ is bigger than the other figures around him because he is the most important. The jewels that are in the middle of the rectangle with the figures are advancing outward making it a three dimensional form as well. When it comes to the back of the book the scale is smaller than the front because of how much greater detail it has. The figures are also small and the same size, no figure is bigger than the other, all seem visually equal to the next. The Lindau Gospels show how important the Gospels are with the beauty of the designs that created it. It is full of rich beauty and symbolism due to the subject matter the manuscript scriptures it contains inside the book. During this time period it shows how religion was significant and recognized by others around the world who are grateful for the Christian faith, that remains so powerful today.

Works Cited

Norman, Jeremy. The Magnificent Upper Cover of the Lindau Gospels (Circa 875). History of

Information.com. 10, April 2018. www.historyofinformation.com/expanded.php?id=2217.

Accessed 21, April 2018.

The Lindau Gospels in Bright. Medieval Histories: News About the Middle Ages. 2 March 2016.

The LindisFarne Gospels Tour: The Lindisfarne Gospels. The British Library (2003).

http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/features/lindisfarne/evangelists.html Accedded 21, April, 2018.

Ross, Nancy Ph. D and Dr. Steve Zucker. “ Lindau Gospels Cover.” YouTube, 9 April 2013,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=269&v=u5vM4rtUSQg. Accessed 21, April 2018